Frederick William Green (March 31, 1911 – March 1, 1987) was an American swing jazz guitarist who played rhythm guitar with the Count Basie Orchestra for almost fifty years.

Green was born in Charleston, South Carolina. He was exposed to music from an early age, and learned the banjo before picking up the guitar in his early teenage years. A friend of his father by the name of Sam Walker taught a young Freddie to read music, and keenly encouraged him to keep up his guitar playing. Walker gave Freddie what was perhaps his first gig, playing with a local community group of which Walker was an organizer. Another member of the group was William "Cat" Anderson, who went on to become an established trumpeter, working with notable figures such as Duke Ellington. Green toured with the Jenkins band as far north as Maine.

After Freddie's parents died when he was in his early teens, he went to New York to live with his aunt and finishing his schooling. Eventually he began to play rent parties and in New York clubs such as the Yeah Man in Harlem and Greenwich Village's Black Cat. Tenor Saxophonist Lonnie Simmons got him one of his first jobs, working with the Night Hawks at the Black Cat. While at the club in 1937, Green was noticed by jazz talent scout John Hammond, who ultimately introduced him to Basie.

Count Basie had just come from Kansas City to New York and was debuting at the famed Roseland Ballroom. Soon after discovering Green, Hammond took Basie, Lester Young, Walter Page, Jo Jones, trumpeter Buck Clayton, and Benny Goodman to hear Freddie at the Black Cat. Although Basie liked his current guitarist, Claude Williams, he let him go in favour of Green, who joined the band after the Roseland engagement. Green cut his first sides with Count Basie and his Orchestra (featuring Page and Jones) for Decca on March 26, 1937, playing rhythm on "Honeysuckle Rose", "Pennies From Heaven", "Swinging At The Daisy Chain", and "Roseland Shuffle".

Throughout his career, Green played rhythm guitar, accompanying other musicians, and he rarely played solos. "His superb timing and ... flowing sense of harmony ... helped to establish the role of the rhythm guitar as an important part of every rhythm section." Green did play a solo on the January 16, 1938, Carnegie Hall concert that featured the Benny Goodman big band. In the jam session on Fats Waller's "Honeysuckle Rose," Green was the rhythm guitarist for the ensemble, which featured Basie, Walter Page (Basie's bassist), and musicians from Duke Ellington's band. After Johnny Hodges' solo, Goodman signalled to Green to take his own solo, which the musician Turk Van Lake described in his commentary on the reissued 1938 Carnegie Hall concert as a "startling move."

As bebop gained momentum in the late 1940s and the emphasis shifted to small group jazz, many big bands fell on hard times. Count Basie was no exception, and in the summer of 1950 he pared the orchestra down to a handful of players. Green found himself unemployed for the first time in 13 years. According to his son, Al, the situation didn't last for long. Shortly after being let go, Freddie showed up with his guitar at one of Basie's gigs insisting he was back in the group. From that moment on, the relationship between Basie and Green was cemented. The unit soon swelled to a septet that included clarinetist Buddy DeFranco and trumpeter Clark Terry.

|

| Ellington, Green & Basie |

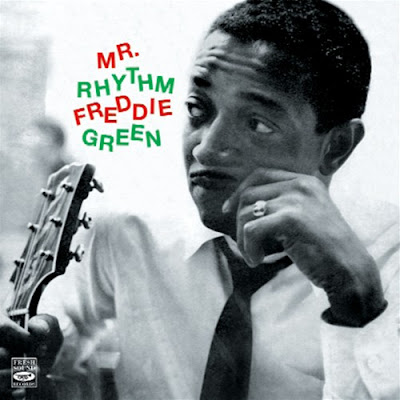

In 1952 Basie was back with another big band, which eventually recorded memorable sessions represented on the reissue album Sixteen Men Swinging. Three years later, Freddie cut the classic Mr. Rhythm under the name Freddie Green and his Orchestra with trumpeter Joe Newman, trombonist Henry Coker, saxophonist Al Cohn, pianist Nat Pierce, drummers Osie Johnson and Jo Jones, and bassist Milt Hinton. The session was a neat blend of rhythmic swing and more bebop-oriented soloing, and much of the material was penned by Green, including "Back And Forth", "Feed Bag", "Little Red", "Free And Easy", and "Swingin' Back".

From the late 1950s into the 1960s the band accompanied such notable vocalists as Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Mel Torme, Sarah Vaughn, Tony Bennett, Billy Eckstine, Sammy Davis Jr., and Judy Garland. In 1962, Green, Basie, bassist Ed Jones, and drummer Sonny Payne recorded the remarkable Count Basie and the Kansas City Seven, with cuts featuring flutists Frank Wess and Eric Dixon.

The mid 1960s and 1970s brought numerous personnel changes to the aggregation; however, it mainly stayed with the Kansas City style swing it did best, despite brief flirtations with more contemporary material such as Beatles' songs and James Bond themes.

Although big band jazz had long been a thing of the past, the group continued to record and tour extensively. Count Basie's death in 1984 closed a rich chapter in big band jazz. He and Green had been good friends onstage and off, and Freddie assumed the helm of the 19 piece group. On March 1, 1987, Freddie Green died of a heart attack after playing a show in Las Vegas. The sad event marked the end of an era in the history of jazz guitar.

(Edited from Freddie Green.org &

Wikipedia)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)